Last weekend I had a brief discussion on the importance of structure when designing pods or stories. It reminded me of an essay I wrote years ago on Poe’s The Purloined Letter (TPL), which Poe himself considered his best tale of ratiocination. What follows is a short recap of my structural analysis.

Introduction

Dupin, C. Auguste, is the detective in Poe’s three tales of ratiocination. In The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841, revised 1845) and The Mysteries of Marie Roget (1842-3), Dupin has to solve a mysterious murder case. In The Purloined Letter (1844/5), first published in The Gift in 1844 and reprinted in an edited version in 1845 in The Tales, Dupin sets out to find what cannot be found and succeeds.

The Dupin stories marked the beginning of the detective genre and were “something in a new key.”1 Dupin became the prototype detective, and the motifs became typical of mystery writing. The clever detective and his “not-so-smart” sidekick, a murder in a locked room or the unjustly accused suspect are common elements and serve as a blueprint for a plethora of mystery stories, from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes to Douglas Adams’s Dirk Gently.

With TPL Poe delivers a philosophical discourse on the methods of truth-finding. Plot is not important, nor are the motifs or the characters. The analysis of how detection is accomplished – the ratiocination is the sole focus of the story. We know who stole the letter and why and what the consequences would be if the purloiner were to use it. The only mystery that remains is how this purloined letter can be found. Returning the letter is irrelevant and not part of the story.

Surrounded by oddities, the characters are limited in their ability to detect the hidden or the obvious. Unfortunately, the person who needs that ability the most is living “amid an absolute legion of oddities” (TPL 331). These oddities, as Poe writes, refer to everything that is beyond comprehension.

The only one who can find the letter is Dupin. The reader is at no point allowed to solve the mystery along with Dupin. You might ask: “Who is this Dupin, and where does he get his powers from?” The Dictionary of Literary Characters gives this answer:

An eccentric genius of extraordinary analytical and deductive powers who rarely leaves his shaded room by day, preferring to walk the night streets in search of the ‘infinity of mental excitement’ offered by observation. He solves mysteries by the power of ratiocination, and is never physically described, perhaps to emphasize his dominance by intellect rather than by emotion. He is poor but of good family, an avid reader, scholarly, romantic and arrogant.2

The supposititious Dupin, however, can only be as ingenious as the author makes him. Two years after publishing TPL, Poe wrote to his friend Philip Cooke:

These tales of ratiocination owe most of their popularity to being something in a new key. I do not mean to say that they are not ingenious – but people think them more ingenious than they are – on account of the method and air of method. In the “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” for instance, where is the ingenuity of unravelling a web which you yourself (the author) have woven for the express purpose of unravelling? The reader is made to confound the ingenuity of the supposititious Dupin with that of the writer of the story.3

Where is the ingenuity of detecting the obvious?” Blinded by oddities, as we are, the obvious answer would be: “There is none.”

It is not the detection itself but the method, which is ingenious: The skill to see the oddities we are surrounded by; to understand the world. Dupin has this mysterious gift. Detection is less bound to the plot but more to the mystery of unravelling the truth and not the web that surrounds it.

Concerning detection David Van Leer writes in his essay The World of the Dupin Tales:

Detection in Poe is less a kind of plot than a form of truth, less a way to tell a story than a means to know the world. The real interest in these tales is not who (or what) done it but what “truth” and “world” are, how they may be reconstructed, and what follows from that reconstruction. (SK 66-7)

Poe constructs his Dupin tales in a way that elevates structure above plot and exemplifies its significance in conveying the “poe-etic” effect to the reader.

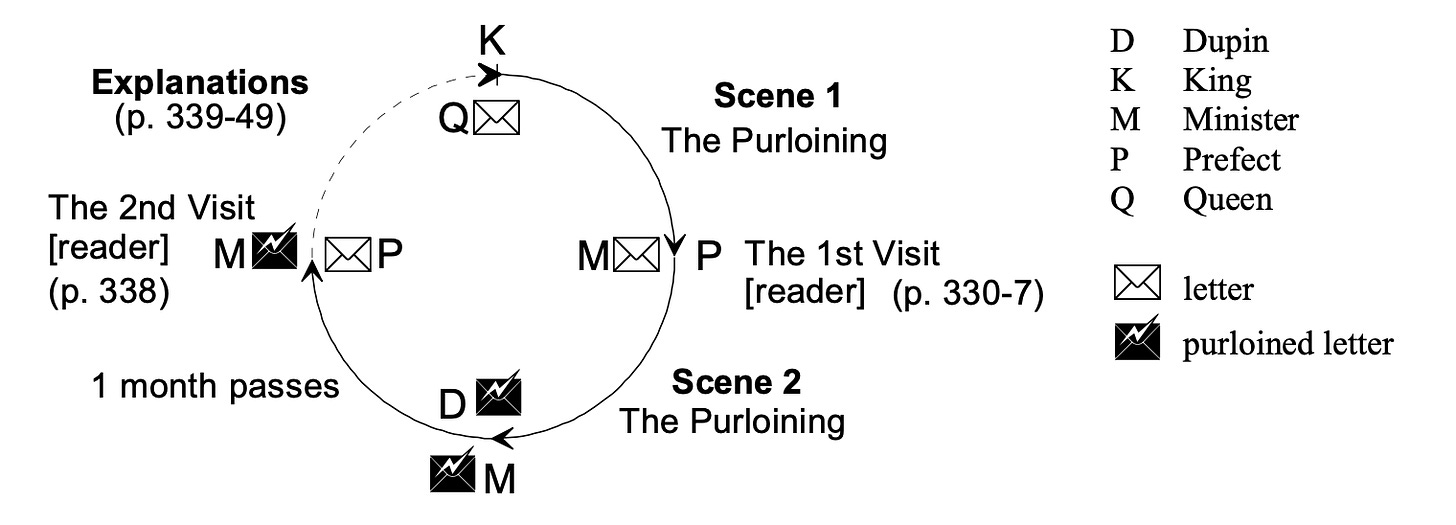

Structure

The story, told by Dupin’s friend, a first-person narrator, evolves around a letter that “has been purloined from the royal apartments” by the Minister under the very eyes of the Queen, unable to prevent it, lest the King notices. The initial theft and the unsuccessful police search that follows are told in retrospect (see [reader] in Figure 1) by the Prefect during his first visit (TPL 330-7). One month later, the Prefect visits Dupin again (TPL 337-9). Frustrated, he recounts his second search and failure to produce the letter. Dupin offers his help, this time in exchange for money. The Prefect pays and Dupin hands him the letter, much to the surprise of the narrator and the Prefect.

I was astounded. The Prefect appeared absolutely thunderstricken. (TPL 338)

Imagine a legion of policemen swarming into the Minister’s place looking for a letter which can be found where one would expect a letter to be, hidden in “plain sight.” Maybe, Poe should have let them find something, a spoon, for instance (as in Monty Python’s Life of Brian).

Dupin proceeds to recount a philosophical analysis of principles of concealment and methods of detection (TPL 339-46) and continues to describe how he has found and subsequently purloined the letter (TPL 346-349). The outcome is predictable, as are the truths Dupin detects. It remains debatable whether the reader is taken by surprise.

Dupin’s actions are not heroic. He purloined the letter and kept it for over a month without returning it, leaving the Queen in constant fear of being exposed by the Minister. To exert power over the person from whom the letter has been purloined, two factors must apply (TPL 333):

a) the purloined letter must not be used

b) the robber must know of the victim’s knowledge of the robber

This applies in the first scene, but not in the second, where the Minister doesn’t know that Dupin has swapped the letters, and while the Minister uses a letter of no importance, Dupin leaves a message hidden inside the replacement. The sole purpose of the message is revenge for “an evil turn, which the Minister did to Dupin at Vienna once” (TPL 348). Since the Minister is acquainted with Dupin’s handwriting, he will know where the letter came from. The motif for the purloining is identical. In both cases, the purloiner wants to obtain and exert power over the victim, only the methods of achieving this goal differ.

The illustration below shows the different stages of the narration and the cyclic and repetitive structure of the text.

Notice the duplication of the purloined letter (6 o’clock) and the ‘double inversion’ of the Queen’s letter (9 o’clock). This re-version of the in-version is not part of the text.

How did the Minister manage to fool the Prefect but not Dupin? Let’s look at the 1845 revised version of TPL:

‘I mean to say,’ continued Dupin, while I merely laughed at his last observations, ‘that if the Minister had been no more than a mathematician, the Prefect would have been under no necessity of giving me this check. I knew him, however, as both mathematician and poet, and my measures were adapted to his capacity, with reference to the circumstances by which he was surrounded. (TPL 343)

Below, the same passage in The Gift: A Christmas, New Year, and Birthday Present, 1845 (September 1844) pages 41-61:

‘I mean to say,’ continued Dupin, while I merely laughed at his last observations, ‘that if the Minister had been no more than a mathematician, the Prefect would have been under no necessity of giving me this check. Had he been no more than a poet, I think it probable that he would have foiled us all.

This establishes the poet as a master of concealment and detection. Poe rewrote the paragraph later and a revised edition was published in the Tales in 1845. It might be improbable that Dupin, master of probability, guilty of doggerel, has such profound knowledge of a poet’s true abilities. Poe might have felt that this was inconsistent with the character of Dupin.

For brevity’s sake, I will skip the next seven pages of in-depth scene analysis and proceed with the conclusion.

The “Poe-etic” Effect

When Dupin mentions he has been guilty of “doggerel” (TPL 334), he means poetry, and according to Poe’s unity of effect rule, the detective has become guilty of the vice of brevity. Poe explicitly states that “a very short poem ... never produces a profound or enduring effect” (TPL 503). Effect may be achieved through repetition. Poe’s structure is repetitive. It also duplicates, as the name Dupin might suggest, and the duplication of the letter might go unnoticed, as well as the double inversion of the original letter, which is concealed in its first inversion and then restored to its original state by a second inversion. The three letters are reminiscent of the triangular model dominant in the repetition scenes.

Regarding the “poe-etic” effect Poe had in mind when he conceived his tales, truth always played a major part. He wrote in his essay The Philosophy of Composition that truth “is far more readily attainable in prose.”

Truth, in fact, demands a precision, and Passion a homeliness (the truly passionate will comprehend me) which are absolutely antagonistic to that Beauty which, I maintain, is the excitement, or pleasurable elevation, of the soul. (TPL 484)

By mirroring the structure and creating difference through the characters’ positions, Poe shows literary truth more as a process than a meaning. Truth is the satisfaction of reason. Poe further writes that passion has a “tendency to degrade rather than to elevate the soul.” Dupin is neither passionate nor is he emotional. He is rational. In the end, it is through Dupin that truth is attained, and thus he creates the basis on which the “poe-etic” effect can be experienced:

And in regard to Truth – if, to be sure, through the attainment of a truth, we are led to perceive a harmony where none was apparent before, we experience, at once the true poetical effect – but this effect is referable to the harmony alone, and not in the least degree to the truth which merely served to render the harmony manifest. (TPL 511-2)

The “poe-etic” effect, as Poe describes it, is “an elevating excitement of the Soul through Supernal Beauty.” It is the poet who “recognizes the ambrosia which nourishes his soul” (TPL 512), which provides the ingredients needed to create the unity of effect.

What about the “poe-etic” effect on the reader then? A question that no doubt has an absolute legion of answers and perspectives from which we are free to choose. Here’s mine:

Truth lies hidden amongst an absolute legion of oddities only a poet can see.

If you like this content, please don’t forget to click the little heart and leave a comment. It helps to keep the pixels from fragmenting. Thank you!

Literature

TPL Poe, E. A. The Fall of the House of Usher And Other Writings. Penguin Classics. England 1994.

BH Bloom, Harold, ed.: Modern Critical Views. Edgar Allan Poe. NY 1985.

MR Muller & Richardson, eds.: The Purloined Poe. Baltimore & London 1988.

SK Silverman, Kenneth, ed.: New Essays on Poe’s Major Tales. Cambridge 1993.

see The Letters of Edgar Allan Poe.

see Dictionary of Literary Characters. Larousse 1994.

from The Letters of Edgar Allan Poe, ed. John Ward Ostrom, 2 vols. Harvard University Press 1948. p. 328.

Deep read, Alexander, thanks! Read this in bed just after waking up. Not sure if that added to the effect. I've never read much Poe (much to my shame), but this was enlightening and complex. Great essay. When I eventually get to the book, it's good to have this as background and reference.

edit: now, can I manage to somehow weave the word "ratiocination" into my work today...